The sake brewing process

The road to Tedorigawa pure filtered sake

—Since our founding in 1870, we’ve dedicated ourselves without compromise to hand-crafted sake,

upholding the traditions of Yamashima, village of sake brewing.

The rice harvest

The elements that make sake brewing possible are the blessings of nature: rice, water, and the smallest of lifeforms. Indispensable to the continued creation of delicious sake is our cooperation with farmers, who protect our local nature and provide us with safe, high-quality rice.

Milling

This process involves milling off the outer portion of the brown rice kernel through abrasion. This part of the rice kernel contains many proteins, fats, ashes, and vitamins that degrade sake quality, making the goal of this process the reduction of these components. Also, the milling ratio describes the initial weight of brown rice versus the weight of milled white after washing: daiginjo sake has a milling ratio 50% or lower, ginjo 60% or lower, and honjozo 70% or lower.

Washing and soaking

In this step, starches clinging to the rice grain are washed away, and the rice is made to soak up a certain volume of water. The amount of water absorbed by the rice has a significant impact on the quality of the steamed rice. At our brewery, we’ve installed automatic rotary rise/immersion equipment in order to thoroughly wash away rice starch and carefully manage the water absorption ratio. With this, we’ve been able to improve the quality and ensured the stability of our steamed rice.

Steaming

Here, we steam the polished and washed white rice to create a mass of steamed rice. The sight of the steam as it gushes and billows up to the ceiling is truly spectacular. By steaming the rice, it becomes easier for the saccharifying (sugar-forming) enzymes to do their job. Also, the addition of heat sterilized the rice, allowing us greater security for the steps to come.

Koji

After steaming the rice, we sprinkle the steamed rice with seed koji to create rice koji. Koji is a very special type of fungus, one that creates enzymes for saccrification. This step is vital to the sake-brewing process, as shown in the brewer’s saying, “Ichi-koji, ni-moto, san-tsukuri” (“First the koji, second the starter, third the mash.”)

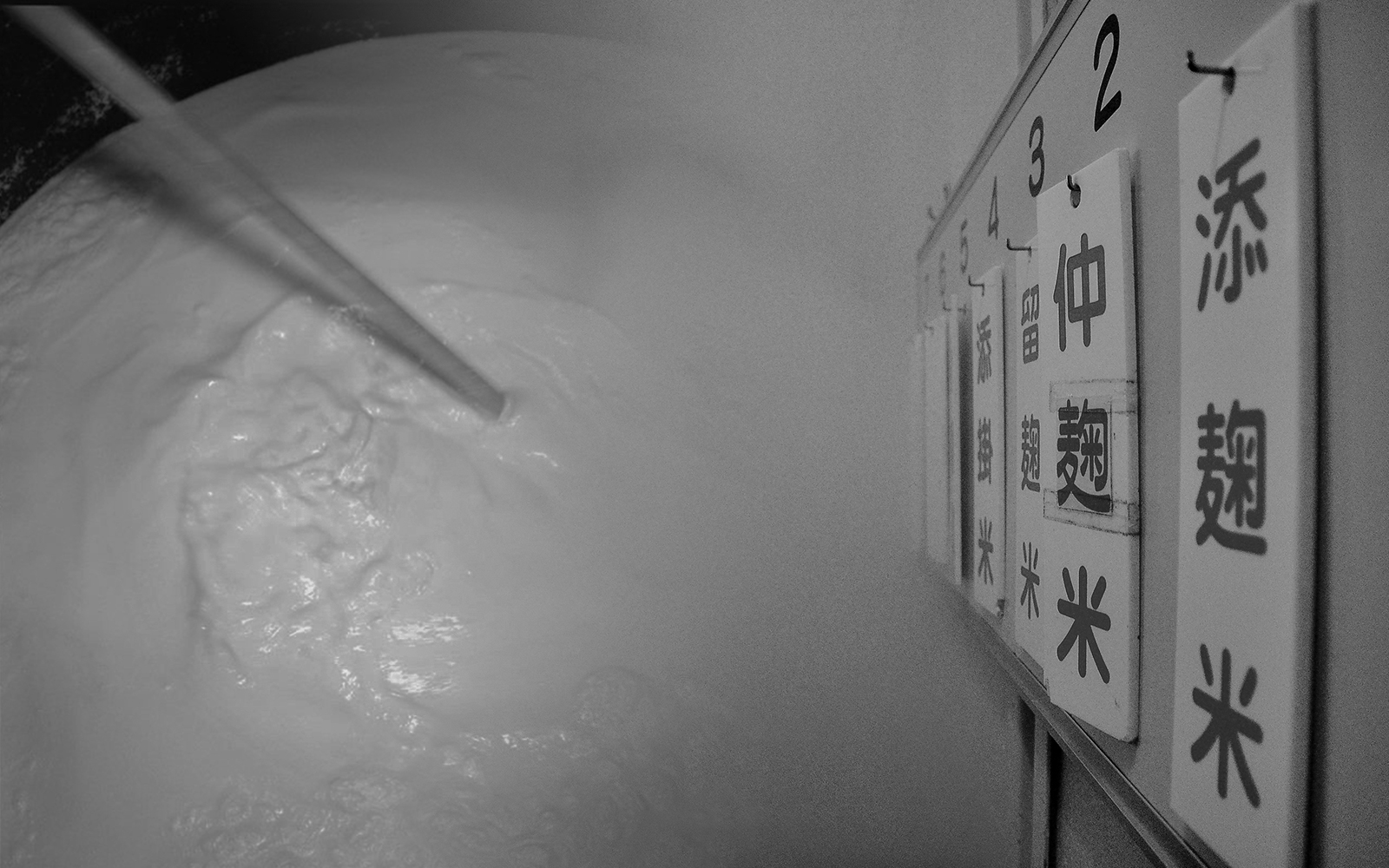

Preparing the yeast starter

In order to purely cultivate a large volume of high-quality yeast, we create a starter called a “shubo” (literally, “mother of sake”) or “moto.” Starters can be broadly classified by method as either a sokujo-type starter (which involves the direct addition of lactic acid) or a kimoto-type starter (the yamahai method is classified as kimoto). Kimoto methods tend to create a sake with more acidity and depth than sokujo.

Three-step mash fermentation

Our mash fermentation is a three-step process effective in encouraging lactic acid and yeast fermentation to create the flavor and experience unique to sake. Each step has its own name: the first is called hatsu-zoe (“first addition”), the second naka-zoe (“mediating addition”), and the third tome-zome (“halting addition”). In this stage of the process, yeast activity converts the glucose created by the saccharifying (sugar-forming) enzymes into alcohol and the flavor components of pure sake emerge. One of the most notable characteristics of sake is the amount of alcohol it produces in only a single round of fermentation.

Pouring off / heating / storage / bottling

Sake brewing begins with the summer rice harvest, and as the year passes we approach at last the time to press out the sake. Once the mash has finished fermenting, we separate the sake from the sake lees in a pouring-off process called jozo. The sake is then filtered, cut with water, and bottled, after which we ship it out.

Sake brewing for your satisfaction

Step by step and across a variety of processes, this is how we create our sake, Tedorigawa.

We bring you our creation, filled with the gratitude we feel toward everyone involved—the farmers who give us their flavorful rice, the merchants and other distributers involved in bringing you our sake in its best possible condition, the enterprises who provide us with caps, bottles, and other necessities… and you, our customer, who has chosen Tedorigawa.